Аллегория Глупости

---

Оригинал взят у  gorbutovich в Аллегория Глупости

gorbutovich в Аллегория Глупости

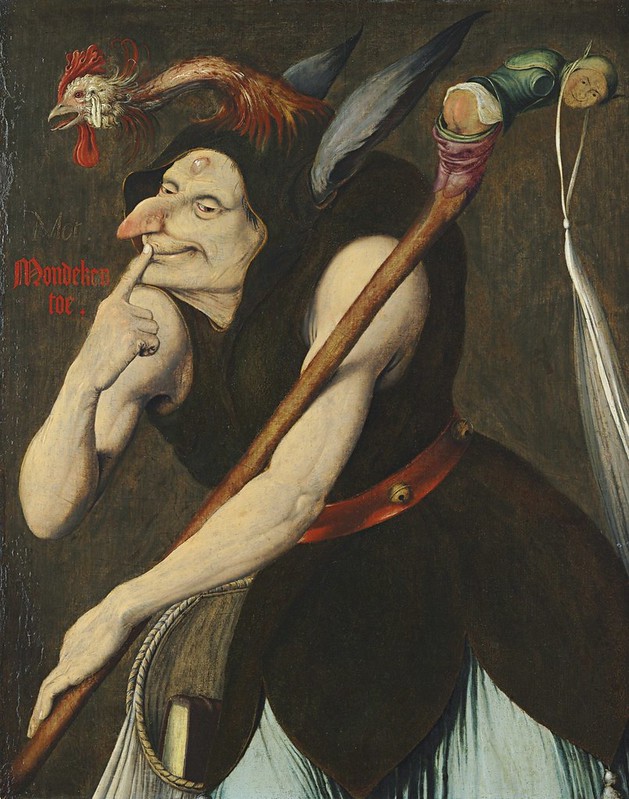

Квентин Массейс. Аллегория Глупости, фрагмент / Quentin Massys (Leuven 1466-1530 Kiel). An Allegory of Folly. Price realised USD 374,500. Christie's. Source

Кликабельно

Квентин Массейс создал картину «Аллегория глупости» вероятно около 1510 года – в то же время когда появилась «Похвала Глупости» Эразма Роттердамского (1466/1469-1536), написанная в 1509 году. Несомненно, что художник и Эразм встречались, так как Массейс написал парные портреты Эразма Роттердамского (Национальная галерея, Рим) и Петра Эгидия (коллекция графа Реднора, замок Лонгфорд, Уилтшир) как дар Томасу Мору в 1517. Эти портреты создали новый живописный сюжет – ученый за работой, который повлиял на Гольбейна и других.

2.

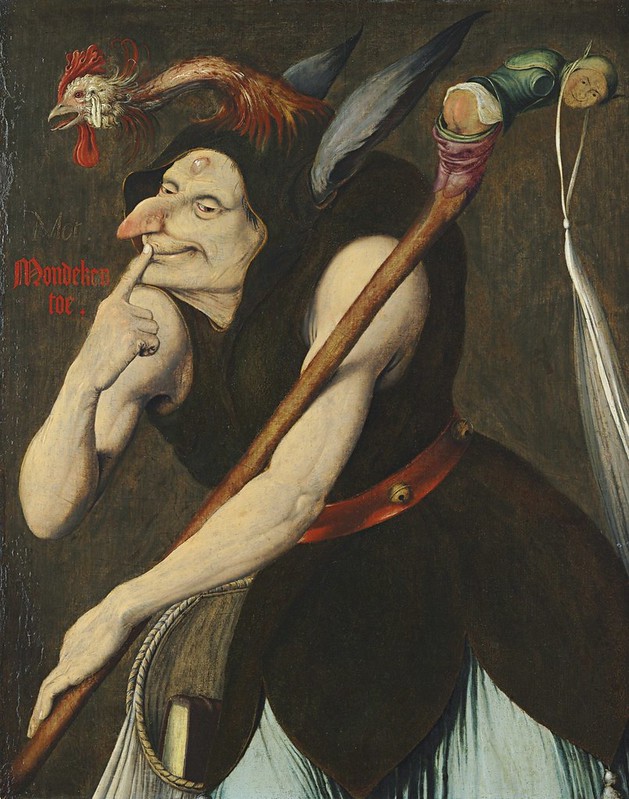

Квентин Массейс. Аллегория Глупости / Quentin Massys (Leuven 1466-1530 Kiel). An Allegory of Folly. Inscribed 'Mot./Mondeken/toe.' (upper left). Oil on panel. 60.3 x 47.6 cm. Lot 66. Price realised USD 374,500. Estimate USD 300,000 - USD 500,000. Christie's. Source

Кликабельно

В начале XVI столетия дураки-шуты часто встречались во время праздников, представлений, карнавалов и при дворах правителей. Иногда Дурак был умственно отсталым и публика развлекалась насмешками и издевательствами над ним. Массейс изобразил своего дурака с наростом на лбу, который, как считалось, содержал «камень глупости», ответственный за глупость или умственную отсталость. В других случаях, однако, глупец был умным и проницательным наблюдателем человеческой натуры, комиком, который использовал одеяния дурака в качестве предлога для сатиры и насмешек. Дурак Массейса был почти точным современником «Похвалы глупости» Эразма, в котором Глупость является на самом деле мудрым и проницательным экспертом по глупости в других. Дураки были популярным предметом как в искусстве, так и в литературе этой эпохи, и сочинение Эразма была особенно важна для гуманистических кругов шестнадцатого века в Антверпене.

Традиционный костюм дурака включает в себя плащ с капюшоном с головой петуха и уши осла, а также колокольчики, прикрепленные к красному поясу. Дурак держит посох, увенчанный маленькой резной фигурой другого дурака в шутовском колпаке. Этот посох можно использовать в качестве куклы для сатирических сцен или пьес. Непристойный жест фигуры в виде стаскивая штанов с зада символизирует оскорбления, связанные с дураками.

Дурак держит палец на губах – это жест молчания, он отсылает к греческому богу молчания Гарпократу, который обычно изображался таким образом. Молчание считалось добродетелью, связанной с мудрыми людьми, такими как философы, ученые или монахи. Здесь, однако, Массейс превращает жест в пародию, сопоставляя его с надписью под головой петуха «Mondeken toe», что означает «держи рот на замке». Позднее выше было добавлено слово «Mot.», вероятно, намек на проститутку – позже в шестнадцатом века или семнадцатом - возможно, это была попытка превратить настоящую аллегорию в фигуру сводницы.

Глупец Массейса становится еще более гротескным из-за его отвратительных уродств. Гротескные фигуры были излюбленной темой художника, регулярно появляясь в его картинах как мучители Христа или в аллегориях Неравных Любовников.

Нидерландский живописец Квентин Массейс / Quentin Massys (1465/6-1530) родился в Лувене, но работал в Антверпене, где стал выдающимся художником своего времени. Несмотря на то, что известна дата его вступления в члены гильдии (1491), о начале его карьеры почти не сохранилось никаких тведений. Его первые датированные работы — это “Алтарь Святой Анны” (Королевский музей, Брюссель, 1507-1509) и “Оплакивание Христа” (Королевский музей изящных искусств, Антверпен, 1508-1511). Массейс продолжал традиции великих мастеров нидерландского искусства, а также хорошо разбирался и в итальянском искусстве – преклонялся перед Леонардо да Винти. Для создания своих пейзажных фонов художник даже поднимался в Альпы, где черпал вдохновение.

Массейс также писал портреты и жанровые сцены. Сатирическое изображение банкиров, сборщиков налогов и алчных торговцев было тесно связано с произведениями великого гуманиста Эразма Роттердамского. У Массейса было два сына-художника: Ян и Корнелиус.

Lot essay

In the early sixteenth century when Massys painted his Allegory of Folly, likely around 1510, fools were still commonly found at court or carnivals, performing in morality plays. Sometimes a fool would be mentally handicapped, to be mocked for the amusement of the general public. Massys has chosen to represent his fool with a wen, a lump on the forehead, which was believed to contain a "stone of folly" responsible for stupidity or mental handicap. In other instances, however, the fool would be a clever and astute observer of human nature, a comedian who used the fool's robes as a pretext for satire and ridicule. Massys's fool was nearly an exact contemporary of Erasmus' Praise of Folly, in which the character of Folly is in fact a wise and astute commentator on folly in others. Fools were a popular subject in both the art and literature of this era and Erasmus' work was particularly important to the sixteenth-century Humanist circles in Antwerp.

The traditional costume of the fool includes a hooded cape with the head of a cock and the ears of an ass, as well as bells, here attached to a red belt. The fool holds a staff known as a marotte, or bauble, topped with a small carved figure of another fool - himself wearing the identifying cap. This staff would have been used as a puppet for satirical skits or plays, and the figure's obscene gesture of dropping his trousers, symbolic of the insults associated with fools, was once overpainted by a previous owner who found it overly shocking.

The gesture of silence, with the fool holding a finger to his lips, refers to the Greek god of silence, Harpocrates, who was generally depicted in this manner. Silence was considered a virtue associated with wise men such as philosophers, scholars, or monks. Here, however, Massys turns the gesture into a parody by juxtaposing it with the inscription 'Mondeken toe', meaning 'keep your mouth shut', beneath the crowing cock's head. Massys is drawing our attention to the Fool's indiscretion. A later hand has added the word 'Mot' above, likely a later sixteenth or seventeenth century reference to a prostitute - this may have been an attempt to turn the present allegory into the figure of a procuress.

Massys' fool is made even more grotesque by his hideous deformities - an exaggerated, beaked nose and hunched back - and thin-lipped, toothless smirk. Grotesque figures were a favourite theme of the artist, making regular appearances in his paintings as tormenters of Christ or in allegories of Unequal Lovers. This reflects an awareness of the grotesque head studies of Leonardo da Vinci, whose drawings had made their way northward from Italy. Indeed, of all Massys's other works, the fool in the present painting is perhaps closest in type to the tormenter directly behind and to the right of Christ in the Saint John Altarpiece - which is, itself, a direct quotation from Leonardo's own drawing of Five Grotesque Heads.

Quinten Massys' early training is a matter of speculation, with scholars suggesting variously that he may have been apprenticed in Antwerp to Dieric Bouts; trained as a miniaturist in his mother's native town of Grobbendonk; or possibly worked for Hans Memling's studio in Bruges. We do know for certain that in 1494, Massys was admitted to the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke as a master painter, and by the end of the century he was operating his own studio with several apprentices, among them his sons Cornelis and Jan. Massys is known for both religious and secular works, and his style became increasingly Italianate in his later career; in turn he is recognized as an influence on such painters as Joos van Cleve, Joachim Patinir and Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Cataloguing & details

Provenance

Norah Smith, Montreal, 1938 as 'Pieter Brueghel'.

Literature

F.F. Sherman, in Art in America, vol. 27, July 1939, p. 147, illustrated, under 'Recent additions to American Private Collections'.

Art News Annual, vol. 37, no. 22, 1939, p. 56, illustrated.

M.L. Wilson, The Tragedy of Hamlet Told by Horatio, Enschede, 1956, pp. 621-22, fig. 83.

E. Tietze-Conrat, Dwarfs and Jesters in Art, London, 1957, pp. 19, 94, fig. 21.

C.A. Wertheim Aumes, Hieronymous Bosch, Holland, 1961.

W. Willeford, The Fool and His Scepter, Evanston, 1969, pp. 6, 29, pl. 2.

L.A. Silver, Quentin Massys (1466-1530), Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1974, pp. 214-15, 355-56.

A. de Bosque, Quentin Metsys, 1975, p. 196, no. 242, illustrated.

S. Poley, Unter de Maske des Narren, Stuttgart, 1981, p. 47, fig. 39.

L.A. Silver, The Paintings of Quinten Massys with Catalogue Raisonné, Montclair, 1984, pp.146-147, 192, 227-228, no.44, plate 135.

C. Gaignebet et al, Art profane et religion populaire au moyen age, Paris, 1985, p. 189.

Görel Cavalli-Bjorkman, 'The Laughing Jester', Nationalmuseum Bulletin, Stockholm, IX, 1985, no. 2, p. 106, fig. 7.

S. Evans, Ben Jonson, PhD diss., University of Kansas, 1991.

P. Lampert, Chronik der Bad Homburger Fastnacht, 1998, p. 100.

M. Slowinski, Blazen, Poznán, cover illustration.

Exhibited

Worcester, Worcester Art Museum, The Worcester-Philadelphia Exhibition of Flemish Painting, 23 February - 12 March 1939.

Philadelphia, J.G. Johnson Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 25 March - 26 April 1939, no. 45.

Grand Rapids, Grand Rapids Art Gallery, Masterpieces of Dutch Art, 7-30 May 1940, no. 45.

Indianapolis, John Herron Art Museum, Holbein and His Contemporaries, 22 October - 24 December 1950, no. 50.

Poughkeepsie, Vassar College Art Gallery, Sixteenth Century Paintings from American Collections, 16 October - 15 November 1964, no. 8.

Northampton, Smith College Museum of Art, Paintings and Sculpture from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Julius S. Held, 1-27 October 1968, no. 33.

Читать: Эразм Роттердамский. Похвала глупости. Перевод с латинского П.К. Губера. Редакция перевода С.П. Маркиша. Статья и комментарии Л.Е. Пинского – М.: Государственное издательство художественной литературы, 1960

Издания на русском (не все):

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвальное слово глупости. – М.-Л. Academia, 1932.

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвала глупости. – М.: Гослитиздат, 1958.

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвала глупости. – М.: Гослитиздат, 1960.

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвала глупости. – М.: Художественная литература, 1983.

Похвала глупости: Пер. с лат. – Калининград, кн. изд-во, 1995.

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвала глупости. – М.: Эксмо-Пресс, 2000.

Роттердамский: Похвала глупости. – М.: Эксмо, 2007.

gorbutovich в Аллегория Глупости

gorbutovich в Аллегория Глупости

Квентин Массейс. Аллегория Глупости, фрагмент / Quentin Massys (Leuven 1466-1530 Kiel). An Allegory of Folly. Price realised USD 374,500. Christie's. Source

Кликабельно

Квентин Массейс создал картину «Аллегория глупости» вероятно около 1510 года – в то же время когда появилась «Похвала Глупости» Эразма Роттердамского (1466/1469-1536), написанная в 1509 году. Несомненно, что художник и Эразм встречались, так как Массейс написал парные портреты Эразма Роттердамского (Национальная галерея, Рим) и Петра Эгидия (коллекция графа Реднора, замок Лонгфорд, Уилтшир) как дар Томасу Мору в 1517. Эти портреты создали новый живописный сюжет – ученый за работой, который повлиял на Гольбейна и других.

2.

Квентин Массейс. Аллегория Глупости / Quentin Massys (Leuven 1466-1530 Kiel). An Allegory of Folly. Inscribed 'Mot./Mondeken/toe.' (upper left). Oil on panel. 60.3 x 47.6 cm. Lot 66. Price realised USD 374,500. Estimate USD 300,000 - USD 500,000. Christie's. Source

Кликабельно

В начале XVI столетия дураки-шуты часто встречались во время праздников, представлений, карнавалов и при дворах правителей. Иногда Дурак был умственно отсталым и публика развлекалась насмешками и издевательствами над ним. Массейс изобразил своего дурака с наростом на лбу, который, как считалось, содержал «камень глупости», ответственный за глупость или умственную отсталость. В других случаях, однако, глупец был умным и проницательным наблюдателем человеческой натуры, комиком, который использовал одеяния дурака в качестве предлога для сатиры и насмешек. Дурак Массейса был почти точным современником «Похвалы глупости» Эразма, в котором Глупость является на самом деле мудрым и проницательным экспертом по глупости в других. Дураки были популярным предметом как в искусстве, так и в литературе этой эпохи, и сочинение Эразма была особенно важна для гуманистических кругов шестнадцатого века в Антверпене.

Традиционный костюм дурака включает в себя плащ с капюшоном с головой петуха и уши осла, а также колокольчики, прикрепленные к красному поясу. Дурак держит посох, увенчанный маленькой резной фигурой другого дурака в шутовском колпаке. Этот посох можно использовать в качестве куклы для сатирических сцен или пьес. Непристойный жест фигуры в виде стаскивая штанов с зада символизирует оскорбления, связанные с дураками.

Дурак держит палец на губах – это жест молчания, он отсылает к греческому богу молчания Гарпократу, который обычно изображался таким образом. Молчание считалось добродетелью, связанной с мудрыми людьми, такими как философы, ученые или монахи. Здесь, однако, Массейс превращает жест в пародию, сопоставляя его с надписью под головой петуха «Mondeken toe», что означает «держи рот на замке». Позднее выше было добавлено слово «Mot.», вероятно, намек на проститутку – позже в шестнадцатом века или семнадцатом - возможно, это была попытка превратить настоящую аллегорию в фигуру сводницы.

Глупец Массейса становится еще более гротескным из-за его отвратительных уродств. Гротескные фигуры были излюбленной темой художника, регулярно появляясь в его картинах как мучители Христа или в аллегориях Неравных Любовников.

Нидерландский живописец Квентин Массейс / Quentin Massys (1465/6-1530) родился в Лувене, но работал в Антверпене, где стал выдающимся художником своего времени. Несмотря на то, что известна дата его вступления в члены гильдии (1491), о начале его карьеры почти не сохранилось никаких тведений. Его первые датированные работы — это “Алтарь Святой Анны” (Королевский музей, Брюссель, 1507-1509) и “Оплакивание Христа” (Королевский музей изящных искусств, Антверпен, 1508-1511). Массейс продолжал традиции великих мастеров нидерландского искусства, а также хорошо разбирался и в итальянском искусстве – преклонялся перед Леонардо да Винти. Для создания своих пейзажных фонов художник даже поднимался в Альпы, где черпал вдохновение.

Массейс также писал портреты и жанровые сцены. Сатирическое изображение банкиров, сборщиков налогов и алчных торговцев было тесно связано с произведениями великого гуманиста Эразма Роттердамского. У Массейса было два сына-художника: Ян и Корнелиус.

Lot essay

In the early sixteenth century when Massys painted his Allegory of Folly, likely around 1510, fools were still commonly found at court or carnivals, performing in morality plays. Sometimes a fool would be mentally handicapped, to be mocked for the amusement of the general public. Massys has chosen to represent his fool with a wen, a lump on the forehead, which was believed to contain a "stone of folly" responsible for stupidity or mental handicap. In other instances, however, the fool would be a clever and astute observer of human nature, a comedian who used the fool's robes as a pretext for satire and ridicule. Massys's fool was nearly an exact contemporary of Erasmus' Praise of Folly, in which the character of Folly is in fact a wise and astute commentator on folly in others. Fools were a popular subject in both the art and literature of this era and Erasmus' work was particularly important to the sixteenth-century Humanist circles in Antwerp.

The traditional costume of the fool includes a hooded cape with the head of a cock and the ears of an ass, as well as bells, here attached to a red belt. The fool holds a staff known as a marotte, or bauble, topped with a small carved figure of another fool - himself wearing the identifying cap. This staff would have been used as a puppet for satirical skits or plays, and the figure's obscene gesture of dropping his trousers, symbolic of the insults associated with fools, was once overpainted by a previous owner who found it overly shocking.

The gesture of silence, with the fool holding a finger to his lips, refers to the Greek god of silence, Harpocrates, who was generally depicted in this manner. Silence was considered a virtue associated with wise men such as philosophers, scholars, or monks. Here, however, Massys turns the gesture into a parody by juxtaposing it with the inscription 'Mondeken toe', meaning 'keep your mouth shut', beneath the crowing cock's head. Massys is drawing our attention to the Fool's indiscretion. A later hand has added the word 'Mot' above, likely a later sixteenth or seventeenth century reference to a prostitute - this may have been an attempt to turn the present allegory into the figure of a procuress.

Massys' fool is made even more grotesque by his hideous deformities - an exaggerated, beaked nose and hunched back - and thin-lipped, toothless smirk. Grotesque figures were a favourite theme of the artist, making regular appearances in his paintings as tormenters of Christ or in allegories of Unequal Lovers. This reflects an awareness of the grotesque head studies of Leonardo da Vinci, whose drawings had made their way northward from Italy. Indeed, of all Massys's other works, the fool in the present painting is perhaps closest in type to the tormenter directly behind and to the right of Christ in the Saint John Altarpiece - which is, itself, a direct quotation from Leonardo's own drawing of Five Grotesque Heads.

Quinten Massys' early training is a matter of speculation, with scholars suggesting variously that he may have been apprenticed in Antwerp to Dieric Bouts; trained as a miniaturist in his mother's native town of Grobbendonk; or possibly worked for Hans Memling's studio in Bruges. We do know for certain that in 1494, Massys was admitted to the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke as a master painter, and by the end of the century he was operating his own studio with several apprentices, among them his sons Cornelis and Jan. Massys is known for both religious and secular works, and his style became increasingly Italianate in his later career; in turn he is recognized as an influence on such painters as Joos van Cleve, Joachim Patinir and Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Cataloguing & details

Provenance

Norah Smith, Montreal, 1938 as 'Pieter Brueghel'.

Literature

F.F. Sherman, in Art in America, vol. 27, July 1939, p. 147, illustrated, under 'Recent additions to American Private Collections'.

Art News Annual, vol. 37, no. 22, 1939, p. 56, illustrated.

M.L. Wilson, The Tragedy of Hamlet Told by Horatio, Enschede, 1956, pp. 621-22, fig. 83.

E. Tietze-Conrat, Dwarfs and Jesters in Art, London, 1957, pp. 19, 94, fig. 21.

C.A. Wertheim Aumes, Hieronymous Bosch, Holland, 1961.

W. Willeford, The Fool and His Scepter, Evanston, 1969, pp. 6, 29, pl. 2.

L.A. Silver, Quentin Massys (1466-1530), Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1974, pp. 214-15, 355-56.

A. de Bosque, Quentin Metsys, 1975, p. 196, no. 242, illustrated.

S. Poley, Unter de Maske des Narren, Stuttgart, 1981, p. 47, fig. 39.

L.A. Silver, The Paintings of Quinten Massys with Catalogue Raisonné, Montclair, 1984, pp.146-147, 192, 227-228, no.44, plate 135.

C. Gaignebet et al, Art profane et religion populaire au moyen age, Paris, 1985, p. 189.

Görel Cavalli-Bjorkman, 'The Laughing Jester', Nationalmuseum Bulletin, Stockholm, IX, 1985, no. 2, p. 106, fig. 7.

S. Evans, Ben Jonson, PhD diss., University of Kansas, 1991.

P. Lampert, Chronik der Bad Homburger Fastnacht, 1998, p. 100.

M. Slowinski, Blazen, Poznán, cover illustration.

Exhibited

Worcester, Worcester Art Museum, The Worcester-Philadelphia Exhibition of Flemish Painting, 23 February - 12 March 1939.

Philadelphia, J.G. Johnson Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 25 March - 26 April 1939, no. 45.

Grand Rapids, Grand Rapids Art Gallery, Masterpieces of Dutch Art, 7-30 May 1940, no. 45.

Indianapolis, John Herron Art Museum, Holbein and His Contemporaries, 22 October - 24 December 1950, no. 50.

Poughkeepsie, Vassar College Art Gallery, Sixteenth Century Paintings from American Collections, 16 October - 15 November 1964, no. 8.

Northampton, Smith College Museum of Art, Paintings and Sculpture from the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Julius S. Held, 1-27 October 1968, no. 33.

Читать: Эразм Роттердамский. Похвала глупости. Перевод с латинского П.К. Губера. Редакция перевода С.П. Маркиша. Статья и комментарии Л.Е. Пинского – М.: Государственное издательство художественной литературы, 1960

Издания на русском (не все):

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвальное слово глупости. – М.-Л. Academia, 1932.

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвала глупости. – М.: Гослитиздат, 1958.

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвала глупости. – М.: Гослитиздат, 1960.

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвала глупости. – М.: Художественная литература, 1983.

Похвала глупости: Пер. с лат. – Калининград, кн. изд-во, 1995.

Роттердамский, Эразм: Похвала глупости. – М.: Эксмо-Пресс, 2000.

Роттердамский: Похвала глупости. – М.: Эксмо, 2007.

Взято: vakin.livejournal.com

Комментарии (0)

{related-news}

[/related-news]